Borehole Helps Change Zambia Forever

A 83-year-old pastor tells the remarkable story of early “center of influence.”

A “center of influence” is a place used by Seventh-day Adventist church members to connect with the local community. A center of influence can be a bookstore, a vegetarian restaurant, or a reading room.

This is the story of one of the first Adventist centers of influence: a simple borehole dug with mission money in 1914.

But the path to the borehole was not simple. It involved a misunderstanding of local customs, a dispute between missionaries, and much prayer, said Simon H. Chileya II, one of the few people still living with direct knowledge of those historical events.

The story began in 1903 when U.S. missionary pioneer William Harrison Anderson arrived in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and found a fertile tract of land that he deemed ideal for establishing a mission station and farm.

Anderson approached the local headman for permission to acquire the land, located about 1 mile (2 kilometers) from the Magoye River in the Monze region, said Chileya, a 83-year-old retired pastor and former leader of the Adventist Church in southern Zambia.

The headman replied that the land had already been offered to a priest who had visited sometime earlier and, wanting to open a mission station, returned to Europe for supplies.

But there was a problem with the land rights, Chileya said. Under local tradition, a new landowner is required to stake a claim for the property, and the priest had failed to do so.

“So, after calling together some other headmen from across the river, it was decided that the place would be given to the Seventh-day Adventist Church,” Chileya said in an interview in his home in Choma, capital of Zambia’s Southern Province.

Claiming the Land

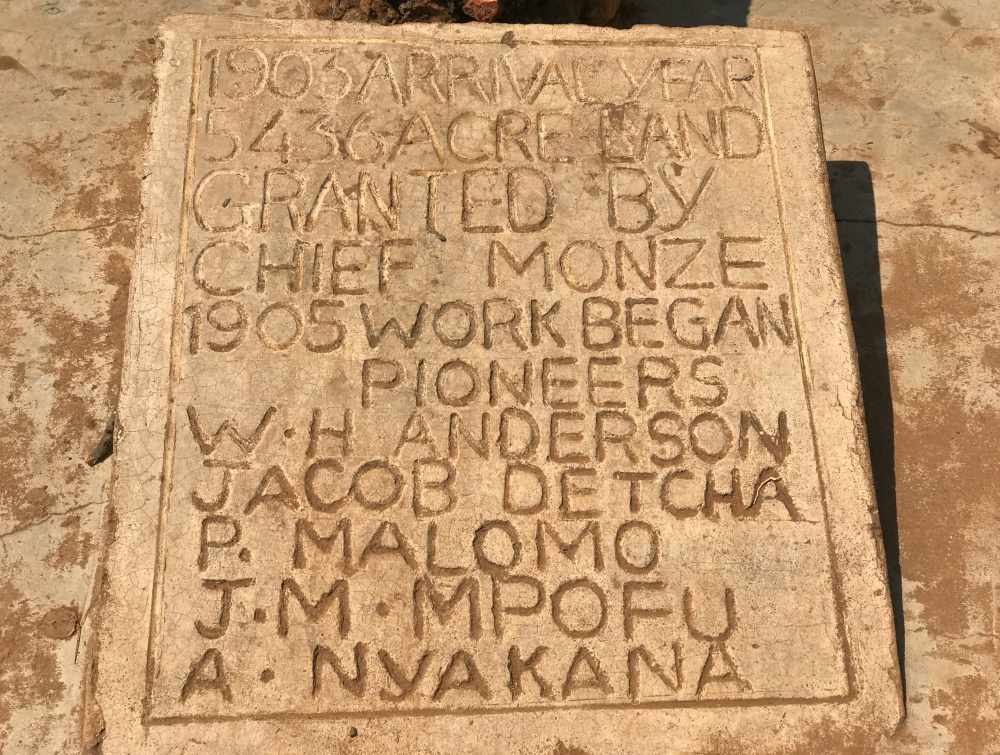

Anderson, following the local custom, claimed 5,000 acres (about 2,025 hectares) of farmland by tearing the bark off a tree and writing an inscription on the trunk.

“The priest did nothing to claim the land and just left,” Chileya said. “But Anderson removed the bark of the tree and cut a message to show that the land was his.”

After that, Anderson traveled to the Solusi mission station in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), which he had set up in 1894, to get supplies for the new mission station. At Solusi, he learned that his father had died and he returned to the United States to tend to family matters.

During the year that he was gone, the priest returned to the Monze region and was told, “Sorry, we have given the land to someone else.”

The priest waited for Anderson and when he arrived, contested the land. The two men couldn’t reach a resolution on the matter, so they appealed to the district commissioner with the local government. He declared that the property belonged to the Seventh-day Adventist Church because Anderson had left the mark on the tree.

Later, Anderson built a permanent marker to corroborate the claim, part of which still stands today.

The priest, meanwhile, was not left empty-handed, Chileya said. The local headman suggested that he speak with the headmen across the river, and the priest received a tract of land where a school and hospital now stand.

Back on the Adventist land, Anderson got to work on setting up the mission station, later known as the Rusangu Mission. His plan was to spend two years on construction, farming, and learning the local Tonga language before opening a school, according to an account in the book “Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists Vol. 4” by Arthur Whitefield Spalding.

Simon H. Chileya II is one of the few people still living with direct knowledge of historical events at Rusangu Mission.

Simon H. Chileya II standing on the porch of his home and speaking with Silas Muabsa of the Southern Africa-Indian Ocean Division.

A small mound, located beside a concrete sign, is what remains of the permanent marker that U.S. missionary pioneer William Harrison Anderson built to corroborate his claim to the land.

A concrete marker commemorating U.S. missionary pioneer William Harrison Anderson's claim to the land at Rusangu Mission.

What is left of the Rusangu Mission borehole, an early "center of influence" that brought many people to Jesus.

Josephat M. Hamoonga of the Southern Zambia Union taking a photo of the borehole at Rusangu Mission. The Anderson marker is in the background.

New School and Borehole

But on Sept. 6, 1905, a day after Anderson arrived, a local young man who spoke a little English approached him as he cut poles to build his hut.

“Teacher, I have come to school,” the young man said.

“School!” exclaimed Anderson, according to the book. “We have no school yet, not even a house. I must study the language, reduce it to writing, make schoolbooks. In two years we may have a school.”

“Are you not a teacher?” asked the young man.

“Yes, that is my work.”

“Then teach me. All this country has heard that you are a teacher and have come to teach us; and here I am. I have come to school.”

Within a month, Anderson was teaching 40 students.

Water, however, proved to be a challenge to the young mission station because it had to be carried from the Magoye River located 1 mile away, Chileya said.

The solution: a borehole.

The borehole was funded by a special General Conference appropriation of $1,000 for improvements to mission in 1914, according to research by Ashlee Chism and David Trim of the General Conference’s Office of Archives, Statistics, and Research.

The borehole, located about 50 yards (50 meters) from Anderson’s permanent marker, became of an early Adventist center of influence, attracting villagers from all around.

“Coming to draw water brought people to the missionaries and gave the missionaries a chance to talk with them,” Chileya said.

Among the people influenced by the missionaries was Paul Choongo, a local farmer and one of the first Adventist converts in the area. Choongo had first-hand knowledge about Rusangu Mission’s origins from the local headmen, and he shared the story with Chileya.

The borehole is now dried up, but the fruit of its labor as a center of influence lives on. The Adventist Church has grown rapidly in Zambia, officially reaching 1 million members in 2015. The territory acquired by Anderson is now occupied by a grade school, a high school, and a thriving university with 4,000 students.

Since its beginnings, Rusangu Mission has been a beacon of light to Zambia and beyond, Chileya said.

“Students came from far away, and when they went back home, they spoke about the gospel,” he said. “They got this from the mission.”

Simon H. Chileya II praises God for His leading through the Rusangu Mission borehole. (Andrew McChesney / Adventist Mission)

Thank you for your mission offerings that support centers of influence today.